Words by Sanaphay Rattanavong

When John Bumstead of Minneapolis left corporate America to start his own laptop repair and refurbishment business, RDKL, Inc. (pronounced ‘Roadkill Incorporated’), he held no creative intentions. “I recycle trash is what I do,” he says. “Recycling is a failure to reuse … a lot [that] gets wasted should really go back into the world.”

For sure, a 2019 UN report tells us of the 50 million tons of e-waste the world produces each year, only 20% of which is formally recycled, effectively sending $62.5 billion worth of rare ore into landfills. So yeah, not just bottles and cans and clap your hands, here.

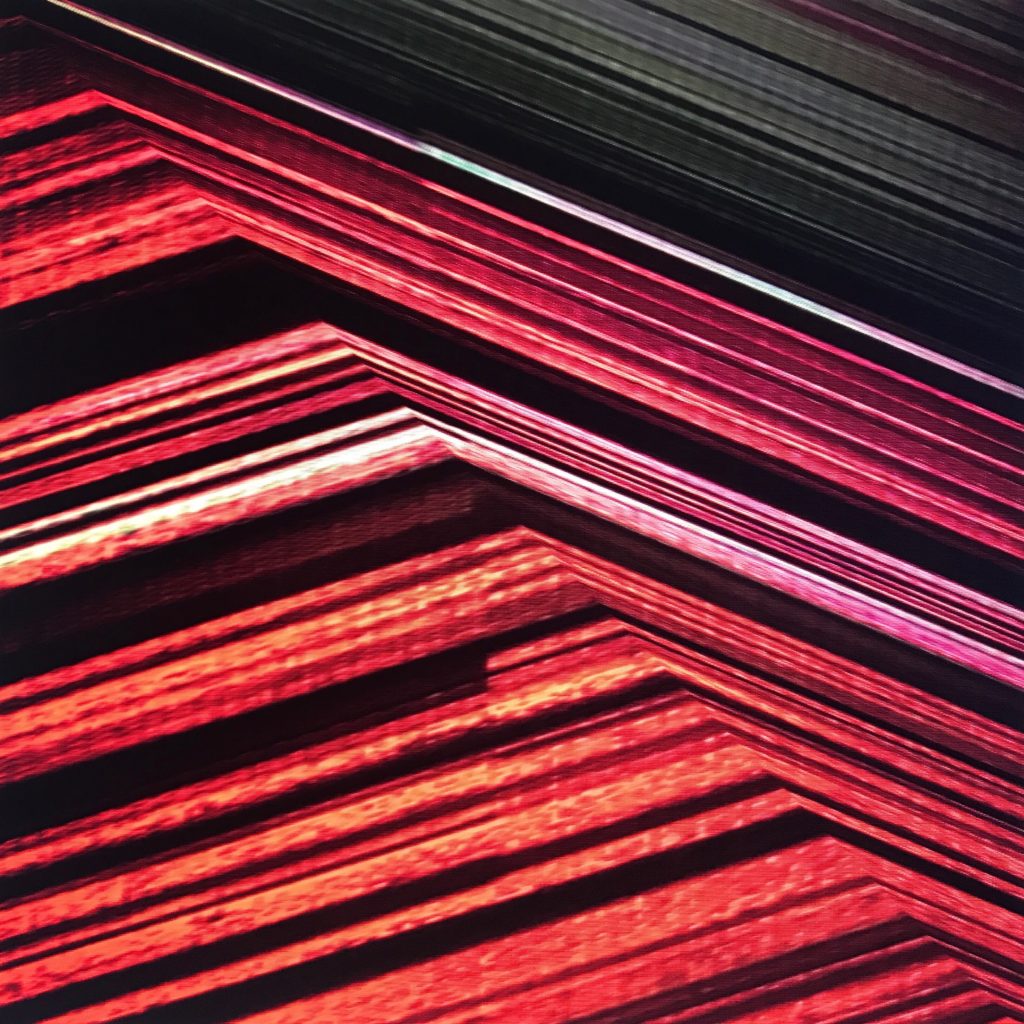

But soon after starting his repair and refurbishment business, Bumstead started to find a second way to return that e-trash back into the world. “Over time,” he explains, “I noticed the graphics processor defects will create artifacts on the screen—which are visual representations of the defect—which were kind of interesting and so I found myself 10 years ago pulling up images behind the broken screen, or behind the defect, and was noticing the defect was acting as kind of a filter, making the image interesting according to its different parameters.”

Bumstead wanted to share what he found with the world, so naturally, he turned to social media. “I started taking pictures of the screens with my photography behind them and posting them to Instagram,” he says.

Not long after, at a repair conference, Bumstead was connected with a writer from Vice. The writer published an article about Bumstead’s work refurbishing macbooks, propelling him into the world of glitch art. He didn’t think of himself as an artist, nor did he at the time know what this glitch art thing was, freely admitting that: “When I started, I really felt like a fraud, because I only had a few techniques, only had a few broken screens that I thought were worth anything—I didn’t feel well-rounded at all.”

He adds that he had friends who were lifelong artists, but weren’t getting nearly as much publicity.

But perhaps Bumstead’s art is more readily understood today than most. “I have the catch-phrase, ‘I’m the guy who makes artwork with [broken] computers,’” he notes (online you will find, “I fix broken computers by turning them into art”). “I think it resonates with people, because at a low-resolution level it’s really easy to understand.”

For another thing, there’s the ubiquity of broken screens in our world, whether in our pockets or someplace more metaphorical.

Lately, John has been using his visibility to curate and promote other glitch artists, while working on his series of work (see below).

* * *

Here are three ways Bumstead transforms his e-trash into art:

1. Play around with broken screens.

“If you can transform [it], you can prolong the life of a thing through changing the purpose,” Bumstead says “If you change [its] purpose, the laptop with the smashed screen is now an art tool. It’s perfect now.”

Bumstead says that a freshly broken screen is best, given it’s made of liquid crystals: When you think of a broken glass of water, the water comes back together, congeals into a blob, as do liquid crystals. “It shatters, you have the most details going on, then it kind of retracts, it comes back”

2. Take advantage of very particular graphics processing unit (GPU) defects.

“It’s a fine line: if you push it too hard it’ll crash and reboot,” he says. So, you must push a little bit at a time.

Ninety-nine percent of machines with bad GPUs will just straight crash. “But because I deal with thousands and thousands of computers,” he explains, “I’m lucky enough to find the rare computer that actually lets you move around and do things while the defects are appearing on the screen.”

Moreover, he says that “You always have to treat it like it’s the last time you’ll use that machine,” because next time you power it on it might not do that again.

3. Manipulate the polarization found in computer and tablet screens.“Turning the filter shows you the whole color spectrum,” he says. Busmtead has a sculpture made of screens that he filters images through. He likes to play the movie Alien on it.

* * *

Now that Bumstead can securely consider himself an artist—a glitch artist, to be specific—he’s free to reflect on the process.

“I think of it as kind of a punk rock thing—50 years ago if you used a computer, you’re programming, because that’s the only interface to it, you’re at the ground level, you’re in the nuts and bolts,” he says. “But [now] you get layers and layers and layers of stuff on top of that, to the point where someone who’s using an iPad, they don’t know they’re using a computer. Then that iPad glitches and what that glitch is, it’s the computer coming out, transcending the layers and saying, ‘Hey, I’m a computer.’ Glitch fundamentally is reminding us that we’re dealing with a computer, however many layers of stuff—it’s reducing us back down to the basic elements.”

As for the glitch art of the future, he says: “As long as we’re using computers, and as long as computers malfunction, I think some semblance of glitch art will always be tracking the technology. It’ll look different in the future, but it’ll be the same kind of representation of reducing whatever is out there to the fundamentals.”

Follow: instagram.com/rdklinc

Glitch Artists Collective:

facebook.com/glitchartistscollective

instagram.com/glitchartistscollective

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.